Food Labelling in the European Union, or Why Your Apple doesn’t have a Label

The label on your food is there to provide you with information about what’s in there, right? That is definitively what the European food labelling rules say. So how does this hold up in the real world? Is all food labelled correctly or are we sometimes misinformed? As we will discover, the following (mis)quote best explains the state of affairs: “All food labels are created equal, but some are more equal than others“.

Why Labelling in the First Place?

Before we go into detail on what is happening in the real world, let’s take a look at why we label in the first place?

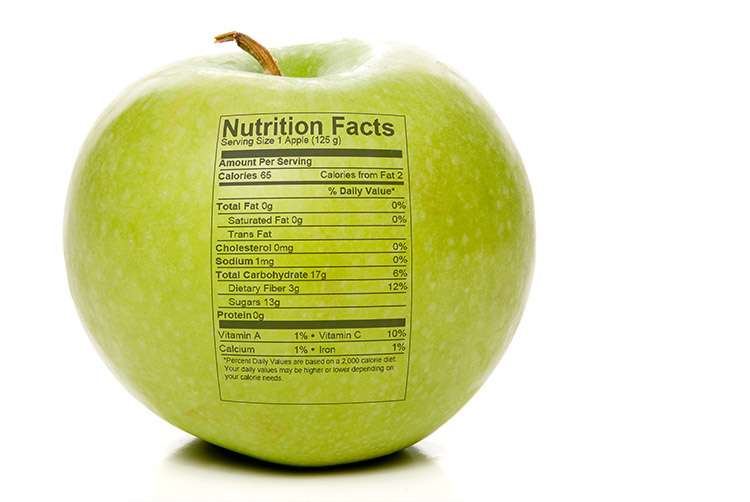

Normally you don’t see a label on an apple. There are of course different nutrients in an apple and generally speaking, you can say that an apple is healthy. With an apple, what you see is what you get. However, when you put an apple in an apple pie or in a juice, you add other ingredients. Because you, the consumer, don’t know exactly how it’s made, the label provides the information about what is in your food.

In the European Union (EU), the European Commission (EC) and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) are tasked with enforcing food labelling rules and regulations. The labelling rules are there to provide you with comprehensive information about the content and composition of food products. Labels help you make an informed choice while purchasing food. Labels let you know what is in the thing you are buying.

Source: http://foods.organicxbenefits.com/

Source: http://foods.organicxbenefits.com/

Food Labelling Claims 101

On the label (and/or packaging) of food, a company is able to make claims. These claims can relate to the nutrients in a food product or to the health benefits that could be a result of eating it.

Nutrition Claims

Nutrition claims are claims about the beneficial nutritional properties in food. They can relate to two things. First, to the energy (calories) that a product provides, e.g. low energy (less than 40kcal). Second, to the nutrients themselves, e.g. high fibre (6 g of fibre per 100 gram). A full list of the possible nutrition claims can be found on the EC website.

Health Claims

There are three categories of health claims that a company can make:

- Functional Health Claims – these include claims that are related to weight loss, psychological effects, and functions of the body.

- Risk Reduction Claims – these are claims about the reduction of risk factors in the development of certain diseases.

- Claims referring to child development.

To make a health claim, you also have to identify the ingredient where this health claim comes from. If you do this you are allowed to choose from a specific list of approved claims. Here is a (somewhat technical) YouTube video about the process:

Example Claims

The EC guidelines contain a comprehensive list of nutrition and health claims that can be made. For two of Queal’s ingredients, Biotin & Calcium, there are already more than 15 claims that are possible to make, such as:

- Biotin contributes to normal psychological function.

- Calcium contributes to normal blood clotting.

- Or, Calcium has a role in the process of cell division and specialisation.

Yes, these are very dry, maybe even boring. And they are not what you normally read on the food you find in the grocery aisle. Heck, these claims may not even be on any products, because one thing that food sellers are thinking about is this: how does this help me sell more products?

Claims in the Wild

It helps when you can say that there is 0% fat in your product. It doesn’t help you when you have to explain how calcium is needed for the maintenance of normal teeth. The (simplified) claims that food companies want to make are therefore at odds with the EC rules and regulations.

Even on a simple fruit bar things can go wrong. Here in The Netherlands, there is a big food chain called Albert Heijn. They make a lot of copy-cat/white-label products and sell them under their own brand. One of these products is a fruit bar. On the front of the strawberry variation it says ‘full of fruit filling’. This claim is in the grey area. 50% of the bar is raspberry filling, but only 5% of that is mashed raspberry and 3% is raspberry concentrate. If this is a total of 8% of the 100% or of the 50% filling isn’t clear.

Where things get dicy for Albert Heijn is the apple fruit bar. It states that it gives a lot of energy. But all authorised claims about energy are related to low/reduced/free of energy. There is no approved claim related to giving you any energy. The better way of representing the energy in a bar could be done by stating the exact energy content (thus not claiming anything). Such a statement, however, would be way less sexy.

Enforcement of the Rules

If there are very strict rules about food regulations, why isn’t everyone sticking to them? That’s because the enforcement may be lacking. The Dutch arm of the EFSA, the NVWA, has many tasks, from checking if you will be poisoned by eating sushi (probably), to making sure that cows aren’t being injected with too many hormones. In their most recent year rapport (Dutch https://www.nvwa.nl/organisatie/jaarverslagen-en-jaarplannen-nvwa) food labelling is mentioned zero times.

And if you look at the big picture it also makes sense. If you can prevent thousands of illnesses by making sure that the supply chain of food is more safe, versus changing a few words on a label, I know what I would focus on. Food labelling may not have the highest priority with the NVWA or other bodies around the EU.

What we do know is that sometimes the rules on food labelling can be enforced very forcefully. A producer of packing told us about the 100.000s of labels that had to be reprinted at his facilities because of the ever-changing rules within the EU. And if you have to change a label on milk, for instance, that means that millions of new cartons have to be made. It’s therefore imperative for companies to be up-to-date with all the food labelling rules and regulations.

Marketing versus Legal

The main incentive for companies is the promotional effect you can get with a claim. And that is where the marketing and legal department may be at odds with each other. If you say your product gives people more beautiful skin, it works better to say it outright, and not to say ingredient X may lead to skin outcome Y. And that is exactly what we heard from a former CMO of a big food company. It’s their task to promote their own product, and if they sometimes have to bend the rules or interpret them broadly, then so be it.

Food labelling rules are very important because they protect consumers, they also help them make an educated choice. And labels on food may not always tell the full story. With some food labelling rules, you may think they are too strict (e.g. that you can’t say a bar is full of energy when you don’t explain where it comes from or how much it is). However, you might think others fail to protect the consumers (e.g. saying there is 0% fat whilst doubling the sugar count in a product). Food labelling will always be in flux and the EFSA & EC will need to constantly keep their eye out for new developments. So that we, as consumers, can always make the best-informed choice.

No Comments